We Are Failing Exploited Young people.

I subscribe to the writer Hanif Kureishi’s Substack blog. I’m a free subscriber and it allows me to read about half of what he writes. For anyone unfamiliar with what has happened to this talented and successful British Pakistani writer of plays, novels, and a harrowing recent memoir, he suffered a catastrophic head/neck injury which left him tetraplegic. After over a year in different hospitals, he is back at home in West London with his loving family, confined to bed or a wheelchair. His wife and children help him to write; he dictates to them. His blogs are always worth reading. He has lost none of his sharpness or acumen.

But the blog that plopped into my inbox yesterday was probably the most traumatic article I’ve read for years. Since it was a free post, open to all, I’m going to reproduce it here. I will discuss it afterwards. It was originally an essay he wrote for Granta in 1992.

‘When I saw them waiting beside their car, I said, ‘You must be freezing.’ It was cold and foggy, the first night of winter, and the two women had matching short skirts and skimpy tops; their legs were bare.

‘We wear what we like,’ Zarina said.

Zarina was the elder of the pair, at twenty-four. For her this wasn’t a job; it was an uprising, mutiny. She was the one with the talent for anarchy and unpredictability that made their show so wild. Qumar was nineteen and seemed more tired and wary. The work could disgust her. And unlike Zarina she did not enjoy the opportunity for mischief and disruption. Qumar had run away from home – her father was a barrister – and worked as a stripper on the Soho circuit, pretending to be Spanish. Zarina had worked as a kissogram. Neither had made much money until they identified themselves as Pakistani Muslims who stripped and did a lesbian double-act. They’d discovered a talent and an audience for it.

The atmosphere was febrile and overwrought. The two women’s behaviour was a cross between a pop star’s and a fugitive’s; they were excited by the notoriety, the money and the danger of what they did. They’d been written up in the Sport and the News of the World.They wanted me and others to write about them. But everything could get out of hand. The danger was real. It gave their lives an edge, but of the two of them only Qumar knew they were doomed. They had excluded themselves from their community and been condemned. And they hadn’t found a safe place among other men and women. Zarina’s temperament wouldn’t allow her to accept this, though she appeared to be the more nervous. Qumar just knew it would end badly but didn’t know how to stop it, perhaps because Zarina didn’t want it to stop. And Qumar was, I think, in love with Zarina.

We arrived – in Ealing. A frantic Asian man had been waiting in the drive of a house for two and a half hours. ‘Follow my car,’ he said. We did: Zarina started to panic.

‘We’re driving into Southall!’ she said. Southall is the heart of Southern England’s Asian community, and the women had more enemies here than anywhere else. The Muslim butchers of Southall had threatened their lives and, according to Zarina, had recently murdered a Muslim prostitute by hacking her up and letting her bleed to death, halal style. There could be a butcher concealed in the crowd, Zarina said; and we didn’t have any security. It was true: in one car there was the driver and me, and in another there was a female Indian journalist, with two slight Pakistani lads who could have been students.

We came to a row of suburban semi-detached houses with gardens: the street was silent, frozen. If only the neighbours knew. We were greeted by a buoyant middle-aged Muslim man with a round, smiling face. He was clearly anxious but relieved to see us, as he had helped to arrange the evening. It was he, presumably, who had extracted the thirty pounds a head, from which he would pay the girls and take his own cut.

He shook our hands and then, when the front door closed behind us, he snatched at Qumar’s arse, pulled her towards him and rubbed his crotch against her. She didn’t resist or flinch but she did look away, as if wishing she were somewhere else, as if this wasn’t her.

The house was not vulgar, only dingy and virtually bare, with white walls, grimy white plastic armchairs, a brown fraying carpet and a wall-mounted gas fire. The ground floor had been knocked into one long, narrow over-lit room. This unelaborated space was where the women would perform. The upstairs rooms were rented to students.

The men, a third of them Sikh and the rest Muslim, had been waiting for hours and had been drinking. But the atmosphere was benign. No one seemed excited as they stood, many of them in suits and ties, eating chicken curry, black peas and rice from plastic plates. There was none of the aggression of the English lad.

Zarina was the first to dance. Her costume was green and gold, with bells strapped to her ankles; she had placed the big tape-player on the floor beside her. If it weren’t for the speed of the music and her jerky, almost inelegant movements, we might have been witnessing a cultural event at the Commonwealth Institute. But Zarina was tense, haughty, unsmiling. She feared Southall. The men stood inches from her, leaning against the wall. They could touch her when they wanted to. And from the moment she began they reached out to pinch or stroke her. But they didn’t know what Zarina might do in return.

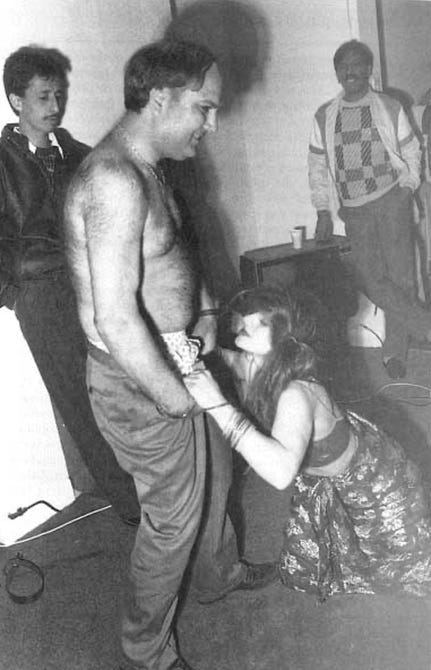

At the end of the room stood a fifty-year-old six-foot Sikh, an ecstatic look on his face, swaying to the music, wiggling his hips at Zarina. Zarina, who was tiny but strong and fast, suddenly ran at the Sikh, threateningly, as if she were going to tackle him. She knocked into him, but he didn’t fall, and she then appeared to be climbing up him. She wrestled off his tweed jacket and threw it down. He complied. He was enjoying this. He pulled off his shirt and she dropped to her knees, jerking down his trousers and pants. His stomach fell out of his clothes – suddenly, like a suitcase falling off the top of a wardrobe. The tiny button of his penis shrank. Zarina wrapped her legs around his waist and beat her hands on his shoulders. The Sikh danced, and the others clapped and cheered. Then he plucked off his turban and threw it into the air, a balding man with his few strands of hair drawn into a frizzy bun.

Zarina was then grabbed from behind. It was the mild, buoyant man who had greeted us at the door. He pulled his trousers off and stood in his blue and white spotted boxer shorts. He began to gyrate against Zarina.

And then she was gone, slipping away as if greased from the bottom of the scrum, out of the door and upstairs to Qumar. The music ended, and the big Sikh, still naked, was putting his turban back on. Another Sikh looked at him disapprovingly; a younger one laughed. The men fetched more drinks. They were pleased and exhilarated, as if they’d survived a fight. The door-greeter walked around in his shorts and shoes.

After a break, Zarina and Qumar returned for another set, this time in black bra and pants. The music was even faster. I noticed that the door-greeter was in a strange state. He had been relaxed, even a little glazed, but now, as the women danced, he was rigid with excitement, chattering to the man next to him, and then to himself, until finally his words became a kind of chant. ‘We are hypocrite Muslims,’ he was saying. ‘We are hypocrite Muslims’ – again and again, causing the man near him to move away.

Zarina’s assault on the Sikh and on some of the other, more reluctant men had broken that line that separated spectator from performer. The men had come to see the women. They hadn’t anticipated having their pants pulled around their ankles and their cocks revealed to other men. But it was Zarina’s intention to round on the men, not turn them on – to humiliate and frighten them. This was part of the act…’