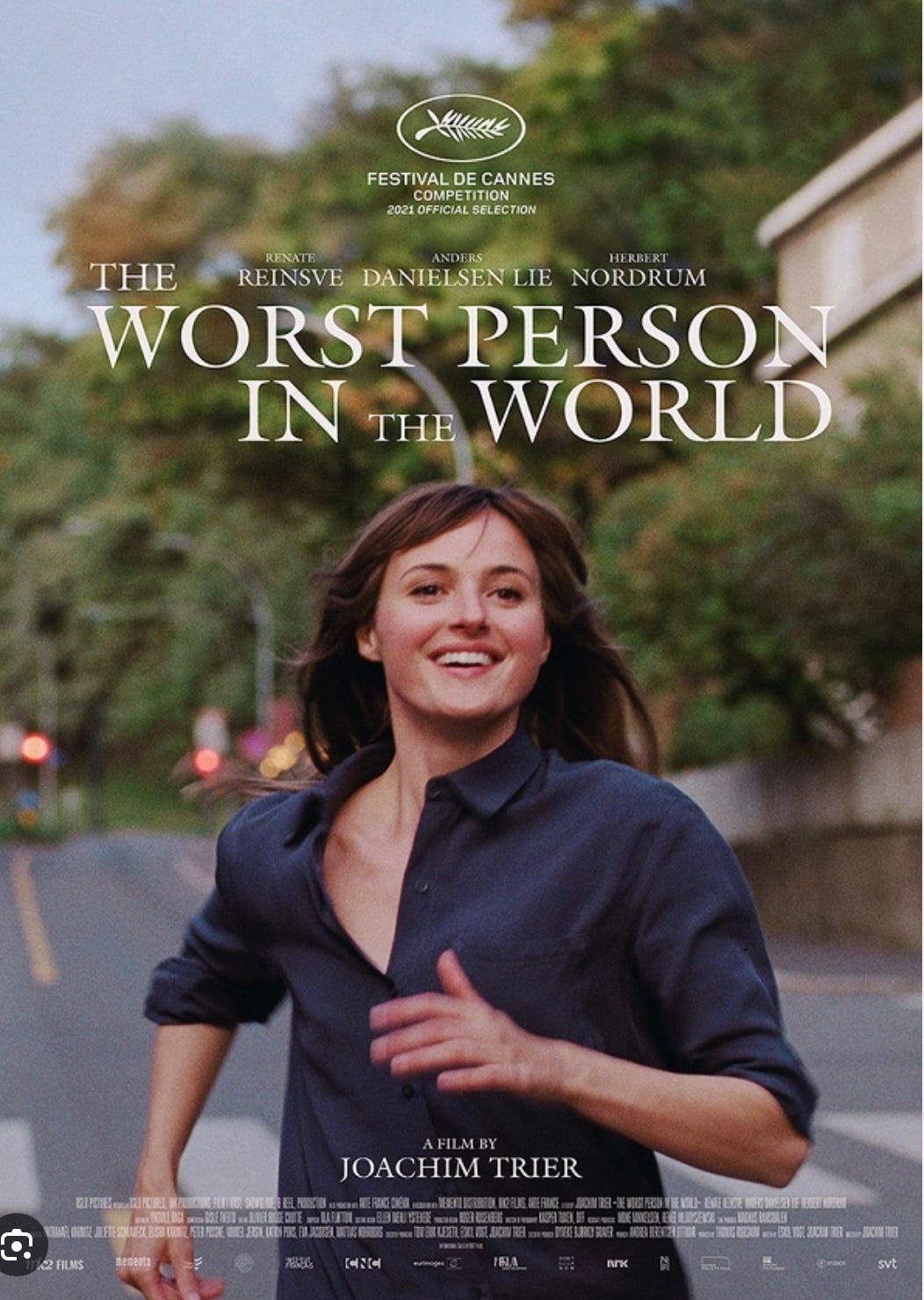

The Worst Person in the World film review

If you like your coming of age stories neat and tidy with proscribed beginning, middle, and end, then this 2021 Norwegian sweep through several years in the life of its female protagonist Julie (Renate Reinsve) may not be for you. For everyone else, it will be a delightful and sometimes painful escape, conjuring up career and love dilemmas of youth as well as posing - and thankfully, not attempting to answer - existential questions about life, love, ethics, selflessness vs inflicting emotional pain on others, and death.

Director Joachim Trier’s third in a loose trilogy (the others were Reprise and Oslo Aug 31), it has already gathered a clutch of awards including Cannes Best Actress 2021 for the magnetic Reinsve, and Amanda Award 2022 for the best screenplay (Trier together with co-writer Eskil Vogt); it impressed the discerning audiences at Cannes and has won a Rotten Tomatoes critics’ rating of 96%.

Divided into 12 brief chapters with a prologue and epilogue, the film follows the mesmeric Julie, a smart but restless young woman, through several years of adulthood, with all their challenges and joys. Julie enrols at medical school simply because her grades are good enough, but quickly becomes disillusioned at the dry world of anatomy, with its rote learning and no time for thinking of the mind. She switches to psychology and then switches again. There is a grim comedic element to the repeated scenes of her announcing her new career intentions to her supportive mother.

Us mortals think of those blessed with stunning, flawless beauty as having the world at their feet, but watching the ease with which Julie moves through her world, the pitfalls also become apparent. If every man you meet wants to have sex with you and many of them fall in love with you, is it a hindrance or a help? It’s not always as clear cut as it may seem, as shoppers faced with endless choices on the shelves may know.

Julie ends up living with a much older successful comic book creator, Aksel. He matches her in intelligence, although his academic conversations with friends sometimes ires her. They are very much in love, and he supports her through her poor relationship with her self-pitying and self-obsessed father. There is a scene in which a seated middle-aged man is telling Julie all about his prostatic symptoms while she nods sympathetically which made me think Julie had gone back and completed medical school. But no, we then see that Aksel is also in the room, and the scene takes on some black humour when we realise this man is Julie’s father, who she has had to travel to see since he always makes excuses about not being able to visit her. Humour quickly morphs to poignancy and pathos when the reality sinks in.

But while Aksel and Julie love each other, comfortably living with someone who is successful also has its drawbacks. With no immediate need to support herself Julie experiences episodes of feeling pointless. She doesn’t love all of his older, married friends. She feels like a spare part at his book launch parties, where he is the object of adoration and she is ignored. Most of all, she feels claustrophobic when he brings up the subject of having children. She wants to live life first. She is free, with no ties or obligations. Why would she give this up?

One of the chapters is entitled ‘Cheating.’ Without giving away what actually happens, this involves the testing of boundaries. I would imagine that anyone watching who is in a relationship, would think that the long, flirtatious, laughter-filled night that follows, with the two characters falling for each other, is far more of a betrayal than any quick, anonymous physical intimacy, although both are obviously devastating.

Once again echoing the problem of being faced with too many choices, the viewer becomes aware that having no imposed discipline on life - no job, no need to earn money, no obligation to do anything for anyone else, no children - may be freeing but it doesn’t always lead to joy.

And we also see how although the grass may be greener, it’s not always more comfortable. It’s easy to be fickle and cast off someone if another seems more immediately appealing, but there are inevitably desirable factors in the known person that the new one can’t fulfil which we realise too late.

The film also raises questions about free will. Just because we can, does it mean we should? Is self actualisation - following our own every whim - always a good thing if it causes pain to others? And does giving up when feeling bored or unseen fulfil us? There is a risk of always looking, always changing, walking on the hearts of others. Even though no one sensible would advocate staying in an unhappy or abusive relationship, there is a reason why the traditional marriage vows include ‘for better or worse’. Sometimes going through difficult times in a relationship strengthens it once they are resolved. And of course, just because we feel empty, it doesn’t mean changing partners will fix us. Fulfilment has to come from the self, not from another.

Nevertheless, there is something joyful in seeing Reinsve’s perfect face lit up with a huge smile, watching her dash across town to a romantic assignment while the rest of the world stands still. She and her beau are the only two people that matter in that moment, an ecstasy shared by anyone who has been madly in love. The only time Julie interacts with her fellow frozen townspeople is when she’s returning rom her blissful date. She sees a couple locked in a kiss on a staircase, and doubles back to move the woman’s palm from her beloved’s arm to his backside. ‘Seize the day’, Julie seems to shout.